As the publication date approaches, an author receives the headshot request from the publisher. The headshot is the photo of the author to be included on the back of the dust jacket of the book. These days that preferred headshot is just that, namely, a photo of the author from the shoulders on up. Some publishers prefer a serious headshot, such as these of bestselling authors John Grisham and James Patterson.

Some prefer a softer look, like this one of Gillian Flynn, author of Gone Girl:

Mine have ranged from serious–

to grinning–

to somewhat contemplative–

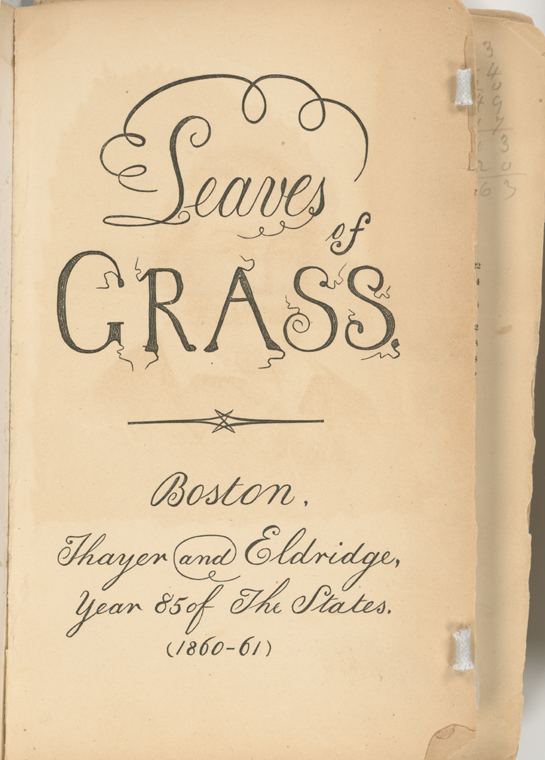

But the coolest author’s photo I’ve ever seen is the one that appeared on the cover of the first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1855. In this new age of self-publishing, it’s interesting to note that Whitman self-published that book of poetry. Although his name appeared nowhere on the cover or title page, the cover of each of the 795 copies of that first edition displayed the following image of the author.

The real Walter Whitman was a city dweller–he lived in Brooklyn–but he purposely dressed for the role of the character introduced by name midway through the first of the twelve untitled poems in the book, as follows:

more modest than immodest.

I came across that “headshot” last night when I took the book down from the shelf to read some of the poems. This was, I confess, the first time I’d opened Leaves of Grass since my 19th Century American Literature class back at Amherst College in the 1970s.

The book is a marvel. As one critic, Ivan Marki, has written:

“The importance of the first edition of Leaves of Grass to American literary history is impossible to exaggerate. The slender volume introduced the poet who, celebrating the nation by celebrating himself, has since remained at the heart of America’s cultural memory because in the world of his imagination Americans have learned to recognize and possibly understand their own. As Leaves of Grass grew through its five subsequent editions into a hefty book of 389 poems (with the addition of the two annexes), it gained much in variety and complexity, but Whitman’s distinctive voice was never stronger, his vision never clearer, and his design never more improvisational than in the twelve poems of the first edition.”

My favorite praise of the book, however, comes from Ralph Waldo Emerson. Whitman had sent him one of those original 795 copies of the first edition. To Whitman’s surprise and delight, Emerson wrote him back. The opening paragraph of that letter, dated July 21, 1855, reads as follows:

DEAR SIR–I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of “LEAVES OF GRASS.” I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy. It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile and stingy nature, as if too much handiwork, or too much lymph in the temperament, were making our western wits fat and mean.

The entire letter, which was published in the New York Tribune later that year, can be read here.

So if you don’t have a dog-eared copy of Leaves of Grass resting forgotten on your bookshelf or stored in the basement in that dusty box of college books, I’d recommend getting hold of a copy. In the interim, check out the Walt Whitman Archive website, where you can read the poems and learn all about the man behind the coolest author headshot ever!

![Grisham190[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Grisham1901.jpg)

![jamesPatterson[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/jamesPatterson1.jpg)

![gillian-flynn[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/gillian-flynn1-237x300.jpg)

![grass_02_lg[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/grass_02_lg1-258x300.jpg)