![collection-dylan-handwriting-01[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/collection-dylan-handwriting-011-1-300x225.jpg)

As the New York Times article on the announcement explains:

Classics from the 1960s appear in coffee-stained fragments, their author still working out lines that generations of fans would come to know by heart. (“You know something’s happening here but you,” reads a scribbled early copy of “Ballad of a Thin Man,” omitting “don’t know what it is” and the song’s famous punch line: “Do you, Mister Jones?”) The range of hotel stationery suggests an obsessive self-editor in constant motion.

That last sentence caught my attention, along with this other one: “There have long been rumors that Mr. Dylan had stashed away an extensive archive.”

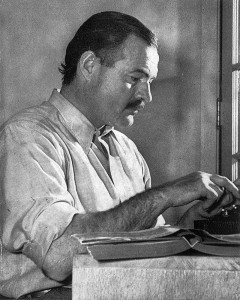

![8df50c_4bc27f9e706f45a9bcb7230eb8431e1f[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/8df50c_4bc27f9e706f45a9bcb7230eb8431e1f1-200x300.jpg) It reminded me of another obsessive self-editor–Ernest Hemingway–and an equally tantalizing rumor. I refer to the mystery of the discarded drafts of the final page of A Farewell to Arms.

It reminded me of another obsessive self-editor–Ernest Hemingway–and an equally tantalizing rumor. I refer to the mystery of the discarded drafts of the final page of A Farewell to Arms.

Near the end of his life, Hemingway sat down with George Plimpton for an interview published in The Paris Review in 1958. When Plimpton asked, “How much rewriting do you do?”, Hemingway famously answered: “It depends. I rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, thirty-nine times before I was satisfied.”

39 times!

Over the next half a century, those 39 discarded endings became part of literary lore, the Holy Grail of 20th Century American literature. And then, in 2012, Scribner announced publication of a new edition of the novel with an appendix containing all of the discarded endings. Turns out there are actually 47, and all had been preserved for decades in the Ernest Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

Well, I couldn’t resist. After reading that article on the Dylan archive, which reminded me of the Hemingway archive, I picked up a copy of that new Scribner edition of A Farewell to Arms. I started by re-reading those sad final two pages of the novel: Frederic’s beloved Catherine goes into labor, suffers complications, undergoes an emergency Cesarean operation, the baby boy dies, and then, after multiple hemorrhages, Catherine dies. Frederic goes out in the hospital hall to talk with the doctor. When he returns to Catherine’s room, one of the two nurses tells him he can’t come in yet. “Yes, I can,” he says, and orders both nurses out of the room. They start to leave, and the book ends with this paragraph:

But after I got them out and shut the door and turned off the light it wasn’t any good. It was like saying good-by to a statue. After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.

A cool and passionless conclusion–quintessential Hemingway. Except for the word “good,” a final paragraph with no adjectives, adverbs, or even commas.

And then I turned to the Scribner appendix, to those 49 discarded endings. They range in length and breadth from just a sentence to several paragraphs.

Perhaps the most haunting is the first, which he labeled “The Nada Ending.” It reads:

That is all there is to the story. Catherine died and you will die and I will die and that is all I can promise you.

More intriguing is No. 7, which he labeled the “Live-Baby Ending”:

I could tell about the boy. He did not seem of any importance then except as trouble and God knows I was better about him. Anyway he does not belong in this story. He starts a new one. It is not fair to start a new story at the end of an old one but that is the way it happens. There is no end except death and birth is the only beginning.

Several endings reference a funeral for Catherine, such as No. 10:

When people die you have to bury them but you do not have to write about it. You meet undertakers but you do not have to write about them.

And then there is No. 34, which he labeled the “Fitzgerald ending,” suggested by his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, according to Hemingway’s grandson Sean:

You learn a few things as you go along and one of them is that the world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. Those it does not break it kills. It kills the very good and very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

When George Plimpton asked him in that Paris Review interview what had stumped him about the ending of A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway answered:, “Getting the words right.” After reading those 47 discarded endings, I’d say he got the words right.