An online discussion among several of my fellow Poisoned Pen Press authors got me thinking about the one decision every fiction author must make before typing CHAPTER 1 at the top of the page. That decision? Who will tell your story?

“Huh,” a baffled reader may wonder, “doesn’t the author tell the story?”

Only rarely. Except for those novels, more typical before the 20th century, where the author occasionally stops the action, pokes his head out from behind the scenery, and addresses you directly, often with a coy, “O gentle reader,” the writer remains, in the jargon of Hollywood, off screen.

So who tells the story? I had to make that decision when, on a dare from my wife Margi, I decided to try to write my first novel, Grave Designs.

But first, a little background:

One familiar storyteller is the”omniscient third-person narrator.” Think of the Book of Genesis: “In the beginning.” That voice comes rumbling down from on high to describe the creation of the earth or reveal the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. No “gentle reader” playfulness there.

One familiar storyteller is the”omniscient third-person narrator.” Think of the Book of Genesis: “In the beginning.” That voice comes rumbling down from on high to describe the creation of the earth or reveal the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. No “gentle reader” playfulness there.

That narrative style is the favorite of many authors. It gives them the ability to dart around the stage and jump inside the heads of any or all of the characters to let us know what they are thinking and what they are up to. In Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the narrator slips into the perspectives of Anna, Vronsky, Karenin, Levin—and even Levin’s dog, Laska (for two chapters)!

There are more constrained versions of third-person narration, the most popular being the third-person subjective, where the narrator can describe the thoughts and actions of one or a few characters but without knowledge of all people, places, and events. Most thrillers are written that way because the author can build suspense by cutting back and forth between the actions of different characters.

At the other end of the spectrum is the first-person narrator, where the entire story is told by a single character. “Here I am,” our narrator announces at the outset. Whatever happens offstage literally happens offstage, since our narrator can only describe what he sees.

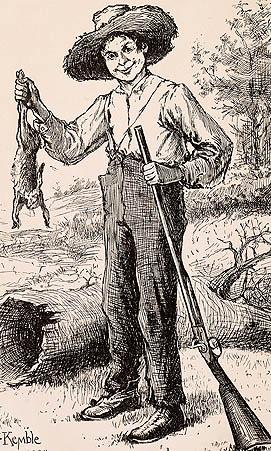

While this narrow scope might seem a handicap for an author, the three contenders for the title Great American Novel are all narrated in the first person, as their authors make clear in their enchanting first sentences. Herman Melville opens Moby Dick: “Call me Ishmael.” Mark Twain opens The Adventures of Huckleberry: “You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter.” And F. Scott Fitzerald opens The Great Gatsby: “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.”

Many authors (including me for two of my novels) fit their storyteller to their story, sometimes opting for first-person and other times for third-person. Charles Dickens chose the former for Great Expectations, opening with the narrator introducing himself: “My father’s family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name being Phillip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.” But he chose the Voice of God for Bleak House, which opens with one of the greatest first chapters in literature.

I had read somewhere that you should write what you know–advice I now realize is terrible. But what did I know back then? I was a young male attorney in a large law firm, and so my detective would be a young male attorney in a large law firm. The idea for the novel? A powerful senior partner dies, his firm discovers a secret codicil to his will setting up a trust fund for the care and maintenance of a grave at a pet cemetery. The mystery? He never owned a pet, and his family has no idea what was in the grave (which will be robbed just days after he dies). My protagonist will be assigned the task of finding out what was in that grave.

Having never written a mystery, I opted for the first-person narrative–a common choice for mysteries. And thus the first word in the first sentence of that first chapter was “I.” They say all of us have at least one whiny, boring autobiographical novel in us, and my young male attorney was soon sounding too much like a whiny version of me. Frustrated, I set the draft aside after 75 pages.

And there it sat for months. Until that day in court as I waited for my case to be called. I watched in dismay as a crusty old male judge taunted and humiliated a young female lawyer. She left the courtroom![TheDeadHand-cover-by-Fervor-Creative-RGB[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/TheDeadHand-cover-by-Fervor-Creative-RGB1-197x300.jpg) in tears. On my way back to the office, I had my author epiphany: my hero would not a young male attorney in that big male-dominated law firm but a savvy, tough young female attorney. Once a prized associate at that firm, she got bored with the corporate clients, fed up with the big firm politics, and did the unthinkable (at least to the firm’s partners): she walked away to set up her own practice. And thus–after several more drafts of those first 75 pages–Rachel Gold’s voice suddenly came alive. Two years later, Grave Designs was in the bookstores.

in tears. On my way back to the office, I had my author epiphany: my hero would not a young male attorney in that big male-dominated law firm but a savvy, tough young female attorney. Once a prized associate at that firm, she got bored with the corporate clients, fed up with the big firm politics, and did the unthinkable (at least to the firm’s partners): she walked away to set up her own practice. And thus–after several more drafts of those first 75 pages–Rachel Gold’s voice suddenly came alive. Two years later, Grave Designs was in the bookstores.

Hard to believe that this month–a quarter of a century later–Rachel and I have reached her tenth novel, The Dead Hand.

![9781464204395_FC-181x276[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/9781464204395_FC-181x2761.jpg)