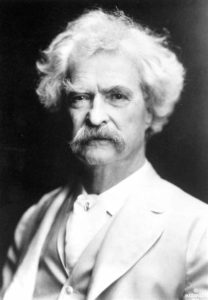

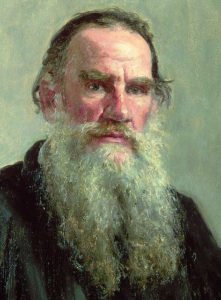

For more years than I’d care to admit, my take on Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina was perfectly summed up by fellow Missourian Mark Twain, who famously defined a “classic” as a novel “that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.”

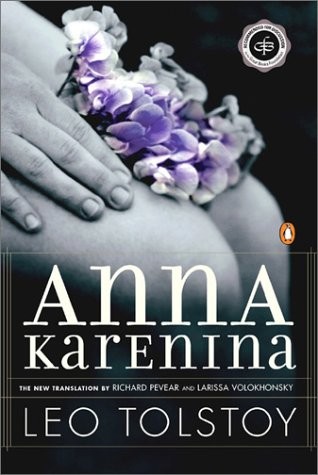

But then a few months ago, while browsing my bookshelves in search of something to read, I once again paused at the spine of my unopened copy of Anna Karenina, this version the award-winning translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky that I had purchased on a whim more than a decade ago. Having recently read two of Tolstoy’s most powerful (and depressing) short stories, The Death of Ivan Ilych and Hadji Murad, I decided it was time to give Anna her due. After all, I told myself, a novel that starts with one of the most famous opening lines in all of literature must be okay.

And so I removed that 817-page small-type tome from the bookshelf, lugged it into the bedroom, and heaved onto the nightstand. There it would remain for just over two months, lifted most nights for about a half-hour-or-so of reading. Like a determined marathoner, I stuck with the novel all the way to that final monologue of Kostya Levin as he walks down the hallway to check on his brother.

The verdict?

I will say this for Tolstoy. The novel lives up to the intriguing promise of its opening line, which reads: “All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Tolstoy gives us several unhappy families: the Karenins, the Vronskys, the Levins, and the Oblonskys, and each one is unhappy in its own way. Moreover, Tolstoy brings many of those family members to life in a remarkably vivid manner. You recognize each one from almost their first appearance, and you come to know them as you read on, and even now, months later, I can visualize most of them. And just as remarkable, many of those characters are ones you would not want to spend any time with. Indeed, some are downright creepy. But alive on the page and in your mind.

But . . . I confess I finished the novel somewhat confused by its title. Yes, Anna Karenina is an important character in the novel, and her illicit (but understandable) love affair with Count Alexi Vronsky drives one of the plot lines that eventually leads to her suicide, but her story does not, at least for me, dominate the novel in the way one might expect of a title character. Think of the roles of the title characters in some of our great works of literature:

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Emma

- The Great Gatsby

- The Count of Monte Cristo

- David Copperfield

- The Adventures of Augie March

- Macbeth, King Lear, and the other Shakespeare tragedies

- and so on and so on.

In other words, the names in those titles are the dominant characters in the stories. Yes, Ophelia is an important character in Hamlet, and her death is every bit as disturbing in that play as Anna’s death is in the Tolstoy novel, but Shakespeare named that play after the main character, and not Ophelia. If we applied that rule to Tolstoy’s novel, the title would be Kostantin Levin, the exasperatingly conflicted but lovable hero of the novel, and a character that many critics view as Tolstoy’s autobiographical doppelganger.

As you have surmised by now, I like Anna Karenina but I didn’t love it. I found the characters far more compelling than the predicaments in which they found themselves. Shame on me.

And, perhaps even more shameful, my favorite character was neither Anna nor Levin, even those two were clearly the most genuine and deeply imagined characters in the novel. No, my favorite character–the one whose appearance always made me smile–was Anna’s brother Stepan Oblonsky, a/k/a Stiva. He is the impish, fun-loving, superficial socialite with a naughty roving eye.

Stiva’s mischief opens the novel. That famous first line sets the stage for the next paragraph, which begins:

Everything was in confusion in the Oblonskys’ house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. This position of affairs had now lasted three days, and not only the husband and wife themselves, but all the members of their family and household, were painfully conscious of it.

And then we meet Stiva:

Three days after the quarrel, Prince Stepan Arkadyevitch Oblonsky–Stiva, as he was called in the fashionable world– woke up at his usual hour, that is, at eight o’clock in the morning, not in his wife’s bedroom, but on the leather-covered sofa in his study. He turned over his stout, well-cared-for person on the springy sofa, as though he would sink into a long sleep again; he vigorously embraced the pillow on the other side and buried his face in it; but all at once he jumped up, sat up on the sofa, and opened his eyes.

“Yes, yes, how was it now?” he thought, going over his dream.

And from that point forward, it will be Stiva who will brighten the scenery and rescue the reader at some of the darkest moments in the novel.

Finally, I should note that my lukewarm endorsement of Anna Karenina is not the unanimous view of the Kahn family. My wife Margi LOVED the novel and places it near the top of her list of great books. So don’t automatically follow Mark Twain’s advice. If you haven’t read it, give it a try. And let me know what you think.