I confess to a failure to appreciate certain works of literature that bask in universal acclaim. One example triggered my apology to Tolstoy for failing to love Anna Karenina–a novel on every list of the greatest works of world literature. And for years I felt a similar bafflement over my lukewarm reaction to Homer’s The Iliad.

I had started that classic excited to finally read the original version of the Trojan Horse episode, that brilliant strategy that ended the 10-year war between the Achaeans and the Trojans. Instead, as I soon discovered, the plot of the Iliad covers just a few weeks in the ninth year of the war and focuses mainly on a ridiculous quarrel between the great warrior Achilles and Agamemnon, who has become leader of all the assembled Greek forces besieging Troy. Agamemnon, in his bloated sense of self entitlement, decides that he hasn’t had enough of the spoils from this war. Specifically, he’s had his eye on a ravishing slave girl given to Achilles. So he takes her for himself. Achilles, now pouting over the loss of his concubine, refuses to fight in the war. Worse, the gods interfere in the outcome of every single battle in the book, each time depending upon the whims of that particular god. And even worse, the Iliad ends before the Trojan Horse scene. Sort of like watching Oceans 11 or The Sting but having the film end before the big climax. It reminded me of my surprised disappointment at the end of David McCullough’s engrossing 1776, when I realized that the Revolutionary War would be continuing beyond the year 1776, and thus beyond the end of the book.

So why have I returned to The Iliad with new appreciation? Because of Hector and his father. Let me explain:

Hector is the great warrior of Troy. He is the son of Priam, who is the king of Troy, and he is the brother of Paris, the handsome bozo who caused the war by seducing Helen, the beautiful wife of Agamemnon’s creepy brother Menelaus, and convincing her to return with him to Troy. Yes, the cause of all the death and devastation suffered in that ten-year war is an angry cuckold seeking revenge.

To me, the two most compassionate scenes in the Iliad are (1) when Hector says goodbye to his wife and baby son before heading off to his battle with the fearsome giant Ajax, and (2) when Priam, at mortal risk, comes alone at night to the tent of Achilles to beg for the corpse of his son Hector that Achilles has killed.

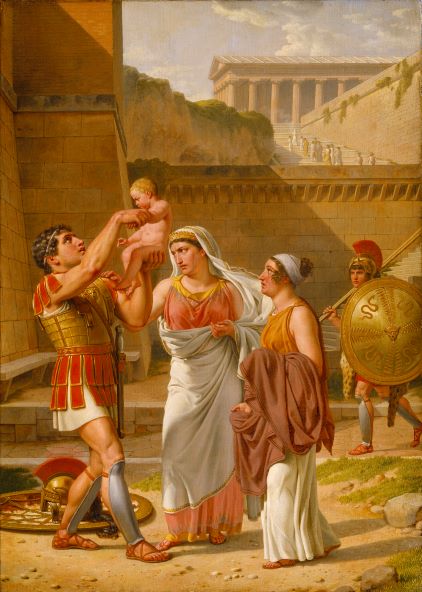

You will not be surprised that I am hardly the first to be moved by these two scenes, both of which have inspired numerous paintings, sculptures, and other works of art.

In that nighttime scene in Achilles’ tent–which occurs in the final book of the Iliad–Priam tearfully begs Achilles to let him take his son Hector’s body back to Troy for a proper funeral. In making his plea, Priam asks Achilles to think of his own father, Peleus, and the deep love between them:

Revere the Gods, Achilles! Pity me in my own right, remember your own father! I deserve more pity. I have endured what no one on earth has ever done before–I put to my lips the hands of the man who killed my son.

The Iliad, Book 24 (Transl. by Robert Fagles 1990)

Both men weep–Priam for his dead son, Achilles for his own father. Achilles agrees to give Hector’s corpse to Priam, who brings the body back to Troy for the huge funeral pyre that is the final scene in the poem, which ends with these words: “And so the Trojans buried Hector breaker of horses.”

But, at least for me, the other scene–the one just before the battle between Hector and and the fearsome Ajax–is even more heart wrenching. Hector has returned to Troy to lead the battle against the Greeks on the plains outside the walls of Troy. We readers know already that he is destined to die in his later battle with Achilles. Hector dons his armor and heads toward the Scaean Gates, the grand entrance to the city where many confrontations have already occurred. But as he reaches those gates, his wife Andromache comes running to meet him, followed by a nurse carrying his infant son Astynax.

Hector turns toward them. “The great man of war,” the poem reads, “breaking into a broad smile, his gaze fixed on his son, in silence.” Andromache, weeping now, pressing against her husband, holding his hand, pleads:

Reckless one, my Hector–your own fiery courage will destroy you! Have you no pity for him, our helpless son? Or me, and the destiny that weighs me down, your widow, now so soon?

The Illiad, Book 6 (Transl. by Robert Fagles 1990)

When she finishes her plea, Hector nods:

All this weighs on my mind too, dear woman. But I would die of shame to face the men of Troy and the Trojan women trailing their long robes if I would shrink from battle now, a coward.

And when he finishes his long speech to his wife, the poem says that “shining Hector reached down for his son–but the boy recoiled, cringing against his nurse’s full breast,” screaming in fear at the site of his father dressed for battle, “terrified by the flashing bronze, the horsehair crest, the great ridge of the helmet nodding, bristling terror.”

And then comes that tender scene that makes me–and perhaps other fathers–teary eyed: “And his loving father laughed, his mother laughed as well, and glorious Hector, quickly lifting the helmet from his head, set it down on the ground, fiery in the sunlight, and raising his son he kissed him, tossed him in his arms, lifting a prayer to Zeus and the other deathless gods”

He asks the gods to grant his son strength and bravery and glory among the Trojans . . .

. . . and one day let them say, He is a better man than his father!

I look at my three sons, all grown men now, and Hector’s final words resonate with me. One day let those who know us say of my three sons, “They are better men then their father.”