Once again my dual lives as a lawyer by day and an author at night have intersected in what is unquestionably a happy new year for all of us–including even Mickey Mouse. Two decades ago the Congress passed an amendment to the Copyright Act that added an additional twenty years to lives of the copyrights in all original works created on and after 1923. Had Congress not acted, hundreds of original works–books, songs, plays, photographs, paintings, poems, and the like–would have fallen into the public domain on January 1, 1999.

And once a work falls into the public domain, it is free for you to use anyway you want. You can make copies (and even sell copies), create derivative works (such as a movie from the novel), market t-shirts with your favorite lines from a poem, or otherwise exploit a work that, if still under copyright, would constitute infringement and expose you to the risk of a lawsuit and financial loss. For example, William Shakespeare’s plays and Jane Austen’s novels and Mark Twain’s novels are all in the public domain. And that means that you don’t need to pay anyone for the right to stage “Hamlet” (or make a movie version) or to download a free copy of Huckleberry Finn or to add zombies to your sequel to Pride and Prejudice.

And once a work falls into the public domain, it is free for you to use anyway you want. You can make copies (and even sell copies), create derivative works (such as a movie from the novel), market t-shirts with your favorite lines from a poem, or otherwise exploit a work that, if still under copyright, would constitute infringement and expose you to the risk of a lawsuit and financial loss. For example, William Shakespeare’s plays and Jane Austen’s novels and Mark Twain’s novels are all in the public domain. And that means that you don’t need to pay anyone for the right to stage “Hamlet” (or make a movie version) or to download a free copy of Huckleberry Finn or to add zombies to your sequel to Pride and Prejudice.

The copyright laws, which date back to the enactment of the U.S. Constitution, are premised on the belief that you will enrich the culture if you give creators a  financial incentive, and that incentive would be a monopoly over all rights in their creations for a limited time. Back then, that limited time was 28 years after creation. By 1978, that “limited time” had grown to the life of the author plus 50 years or 75 years total for a work of corporate authorship (such as a motion picture). And then, in 1998, pursuant to “The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act” (also derisively labeled “The Mickey Mouse Protection Act” by critics who viewed the extension as a money-grubbing attempt by The Walt Disney Company to maintain their monopoly over Mickey Mouse), Congress added another 20-year term to all works made during or after 1923. In other words, copyrighted works created in 1923, which would have fallen into the public domain on January 1, 1999, would now remain under copyright until January 1, 2019.

financial incentive, and that incentive would be a monopoly over all rights in their creations for a limited time. Back then, that limited time was 28 years after creation. By 1978, that “limited time” had grown to the life of the author plus 50 years or 75 years total for a work of corporate authorship (such as a motion picture). And then, in 1998, pursuant to “The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act” (also derisively labeled “The Mickey Mouse Protection Act” by critics who viewed the extension as a money-grubbing attempt by The Walt Disney Company to maintain their monopoly over Mickey Mouse), Congress added another 20-year term to all works made during or after 1923. In other words, copyrighted works created in 1923, which would have fallen into the public domain on January 1, 1999, would now remain under copyright until January 1, 2019.

But now the freeze has ended. If you’d like to see the lists of creative works that fell into the public domain shortly after we all uncorked champagne bottles on New Year’s Eve, you can go here or here. And if you’d like to read my legal blog post on the topic, you can go here.

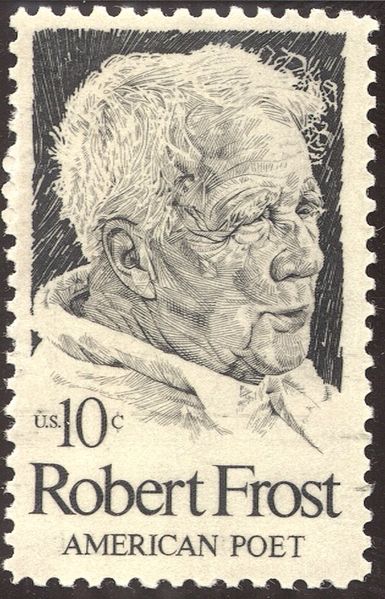

As for the title of this post, many (or perhaps all) of you recognize that line from one of Robert Frost’s most powerful poems. That particular poem had actually fallen into the public domain seven years before the 1998 extension. But another powerful–indeed, magical–Frost poem is among the hundred of works that fell into the public domain, free to all, on January 1, 2019. If you’d like to put that poem on t-shirts or greeting cards or use it as lyrics for a song, go for it. And, if like me, you love that poem so much that you want to end your blog post with it, have at it! Enjoy:

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

By Robert FrostWhose woods these are I think I know.His house is in the village though;He will not see me stopping hereTo watch his woods fill up with snow.My little horse must think it queerTo stop without a farmhouse nearBetween the woods and frozen lakeThe darkest evening of the year.He gives his harness bells a shakeTo ask if there is some mistake.The only other sound’s the sweepOf easy wind and downy flake.The woods are lovely, dark and deep,But I have promises to keep,And miles to go before I sleep,And miles to go before I sleep.