![trollope_1795133c[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/trollope_1795133c1-300x253.jpg)

I am currently reading Can You Forgive Her, a satirical depiction of the 19th-century British version of our 1%–or, in Trollope’s words “the Upper Ten Thousand of this our English world.” As Alexander Larman wrote in The Guardian in 2012 upon publication of a new edition of the novel, “Trollope’s account of a society in which money, breeding and influence, rather than skill or integrity, are the primary routes into power is unpleasantly familiar.”

I am currently reading Can You Forgive Her, a satirical depiction of the 19th-century British version of our 1%–or, in Trollope’s words “the Upper Ten Thousand of this our English world.” As Alexander Larman wrote in The Guardian in 2012 upon publication of a new edition of the novel, “Trollope’s account of a society in which money, breeding and influence, rather than skill or integrity, are the primary routes into power is unpleasantly familiar.”

As with many popular novelists of every era, including ours, Trollope amused his readers with witty allusions to current events and gossip, most of which completely escape a modern reader–and especially one in the United States. But every once in awhile you come across an allusion with just enough meat to hook your curiosity.

Such was the case earlier this week as I was reading Chapter 33 of Can You Forgive Her. That’s where we meet Lady Monk, the wealthy wife of Sir Cosmo Monk:

“Lady Monk was a woman now about fifty years of age, who had been a great beauty, and who was still handsome in her advanced age. Her figure was very good. She was tall and of fine proportion, though by no means verging to that state of body which our excellent American friend and critic Mr. Hawthorne has described as beefy and has declared to be the general condition of English ladies of Lady Monk’s age. Lady Monk was not beefy. She was a comely, handsome, upright, dame,—one of whom, as regards her outward appearance, England might be proud,—and of whom Sir Cosmo Monk was very proud.”

Beefy? As described by “our excellent American friend and critic Mr. Hawthorne”? Nathaniel Hawthorne? Huh?

I did a little digging. Here’s what I learned:

![hawthorne[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/hawthorne1-300x181.jpg)

“I have heard a good deal of the tenacity with which English ladies retain their personal beauty to a late period of life; but (not to suggest that an American eye needs use and cultivation before it can quite appreciate the charm of English beauty at any age) it strikes me that an English lady of fifty is apt to become a creature less refined and delicate, so far as her physique goes, than anything that we Western people class under the name of woman. She has an awful ponderosity of frame, not pulpy, like the looser development of our few fat women, but massive with solid beef and streaky tallow; so that (though struggling manfully against the idea) you inevitably think of her as made up of steaks and sirloins. When she walks, her advance is elephantine. When she sits down, it is on a great round space of her Maker’s footstool, where she looks as if nothing could ever move her.”

Ouch! And that’s only beginning. Here’s what he has to say about her poor husband:

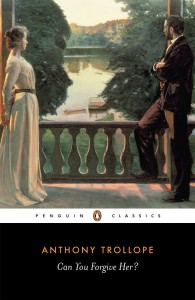

“I wonder whether a middle-aged husband ought to be considered as legally married to all the accretions that ![694242_f520[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/694242_f5201-300x140.jpg) have overgrown the slenderness of his bride since he led her to the altar, and which make her so much more than he ever bargained for! Is it not a sounder view of the case, that the matrimonial bond cannot be held to include the three fourths of the wife that had no existence when the ceremony was performed?”

have overgrown the slenderness of his bride since he led her to the altar, and which make her so much more than he ever bargained for! Is it not a sounder view of the case, that the matrimonial bond cannot be held to include the three fourths of the wife that had no existence when the ceremony was performed?”

![punch1[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/punch11-221x300.jpg) As you might imagine, that essay was not received well across the pond. The review of the book in the October 17, 1863 issue of Punch magazine (also available online), under the title “A Handful of Hawthorne,” opens with a blast aimed at the entire collection of essays. Addressing himself to Mr. Hawthorne, the critic states that “you have put all the caricatures and libels upon English folk, which you have collected while enjoying our hospitality. Your book is thoroughly saturated with what seem ill-nature and spite.”

As you might imagine, that essay was not received well across the pond. The review of the book in the October 17, 1863 issue of Punch magazine (also available online), under the title “A Handful of Hawthorne,” opens with a blast aimed at the entire collection of essays. Addressing himself to Mr. Hawthorne, the critic states that “you have put all the caricatures and libels upon English folk, which you have collected while enjoying our hospitality. Your book is thoroughly saturated with what seem ill-nature and spite.”

Ah, but the real fun–and outrage–begins when the reviewer turns to, and quotes from, that lengthy passage about English women. Here is his response:

“Well painted, Nathaniel, with a touch worthy of Rubens, who was we think your great uncle, or was it Milton, or Thersites, or somebody else, who, in accordance with American habit, was claimed as your ancestor. Never mind, you are strong enough in your own works to bear being supposed descended from a gorilla, were heraldry unkind. Mr. Punch makes you his best compliments on your smartness, and on the gracious elegance of your descriptions of those with whom you are known to have been so intimate, and he hopes that you will soon give a world a sequel . . . in the form of an autobiography. For he is very partial to essays on the natural history of half-civilized animals.”

Ra-ta-boom!

And thus the background to Trollope’s reference to “our excellent American friend and critic Mr. Hawthorne.” And a salute to the wonders of the Internet, where this kind of detective work can be accomplished in less than an hour at your computer instead of multiple hours–or even days–in the library.