Earlier this month, the St Louis Jewish Film Festival asked me to introduce the screening of Fire Birds, an Israeli murder mystery set in Tel Aviv (with English subtitles). To prepare my introductory remarks, I watched the film. Somewhere toward the middle of the movie, I had my epiphany. “Thank you, Mr. Hammett,” I said.

Let me explain.

Some of our nation’s most influential exports over the past century have been our arts and culture. In music, for example, we gave the world the blues, jazz, and rock. In fashion, our contributions have included Levi jeans and Chuck Taylor sneakers.

And in literature, one of our most influential exports has been the hard-boiled detective novel. Although Edgar Allan Poe is often credited with inventing the mystery story, by the 1920s the ascendant version was the so-called British cozy, best exemplified by Dorothy Sayers’ charming gentlemen detective Lord Peter Wimsey, a dilettante who solved mysteries for his own amusement.

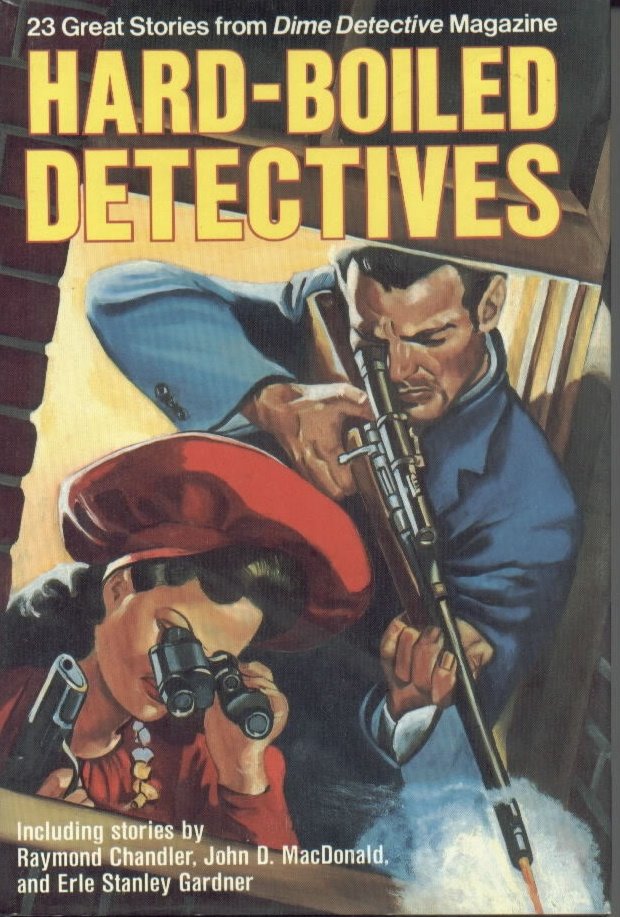

And then![29056[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/290561-158x300.jpg) along came the American hard-boiled crime novel, whose pioneers included Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James Cain. Unlike the heroes in the British mysteries, this American genre’s typical protagonist was a tough, cynical detective familiar with graphic violence and sordid urban corruption. Marked by fast-paced, slangy dialogue, the hard-boiled detective novel has been one of our most popular literary exports and now includes bestselling authors around the world.

along came the American hard-boiled crime novel, whose pioneers included Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James Cain. Unlike the heroes in the British mysteries, this American genre’s typical protagonist was a tough, cynical detective familiar with graphic violence and sordid urban corruption. Marked by fast-paced, slangy dialogue, the hard-boiled detective novel has been one of our most popular literary exports and now includes bestselling authors around the world.

Which brings me to Film Noir, the cinematic version of the hard-boiled mystery novel. The genre got its start in in the 1940s with film versions of those novels, including The Maltese Falcon, The Postman Always Rings Twice and The Third Man. Over the decades since World War II, the genre has spread to filmmakers around the world and has continued to evolve in this country through award-winning “Neo-Film Noir” creations that include Chinatown, Blood Simple, The Big Lebowski, and Blade Runner.

So what makes a film a Film Noir? While that question has inspired numerous critical essays, such as this one and this one, the basic elements can be simply stated as follow:![movie_36549[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/movie_365491-200x300.jpg)

- a crime–usually a murder–often occurring near the beginning of the film;

- a cynical detective, usually flawed, often outside the norm (such as, say, kicked off the police force for insubordination or drug abuse);

- at least one femme fatale;

- the seemingly straightforward crime that turns out to be far more complex as our detective follows clues on an odyssey through the dark underworld of the city; and

- lots of flashbacks, occasionally confusing.

Every one of these elements is on full display in Fire Birds. As the movie opens, an old man’s body is found![5543433-6950[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/5543433-69501-209x300.jpg) floating in a river in Tel Aviv with three stab wounds to the chest and a number tattooed along his forearm. The police detective assigned to the case, himself a second generation Holocaust survivor, reluctantly accepts the case and struggles to bring it to a quick close. He soon learns that the number tattooed on the dead man’s arm actually belongs to a Holocaust survivor who died years ago.

floating in a river in Tel Aviv with three stab wounds to the chest and a number tattooed along his forearm. The police detective assigned to the case, himself a second generation Holocaust survivor, reluctantly accepts the case and struggles to bring it to a quick close. He soon learns that the number tattooed on the dead man’s arm actually belongs to a Holocaust survivor who died years ago.

As we learn in the flashbacks, the dead man had sought a ‘membership card’ to what one femme fatale labels the most horrible club in the world: the club of Holocaust survivors. Despite his age, the dead man’s charm was evident as he searched the obituaries for widows (a/k/a elderly femme fatales) to beguile. As the story interweaves past and present, we witness each man’s struggle to rejoin the society which rejected him.

This award-winning film certainly works on its own, but fans of hard-boiled detective fiction and Film Noir will recognize the distinctly American lineage of Fire Birds. See it if you get a chance.