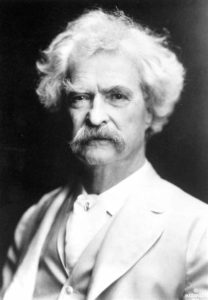

As a copyright lawyer, I have always smiled at the following quote from Mark Twain:

“Only one thing is impossible for God: To find any sense in any copyright law on the planet.”

And for those seeking to find any sense in that law, no realm is more of a challenge than the doctrine of “fair use,” which I have sarcastically referred to in the past as a copyright lawyer’s full employment act. And once you find yourself in that fog of war along the copyright border between “fair use” and infringement, be careful or you may stumble into the swamp of appropriation art, where you will find yourself swimming with the likes of Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Roy Lichtenstein, and, of course, Andy Warhol.

Which brings me to a fascinating recent Supreme Court decision pitting the Andy Warhol Foundation against Lynn Goldsmith, described by Justice Sonya Sotomayer as a “a trailblazer” who “began a career in rock-and-roll photography when there were few women in the genre. Her award-winning concert and portrait images, however, shot to the top. Goldsmith’s work appeared in Life, Time, Rolling Stone, and People magazines, not to mention the National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art. She captured some of the twentieth century’s greatest rock stars: Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, and, as relevant here, Prince.”

A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to meet with Ms. Goldsmith. And before I left her office that afternoon, she sent me home with a copy of Rock and Roll, a remarkable book of her photographs of those rock stars.

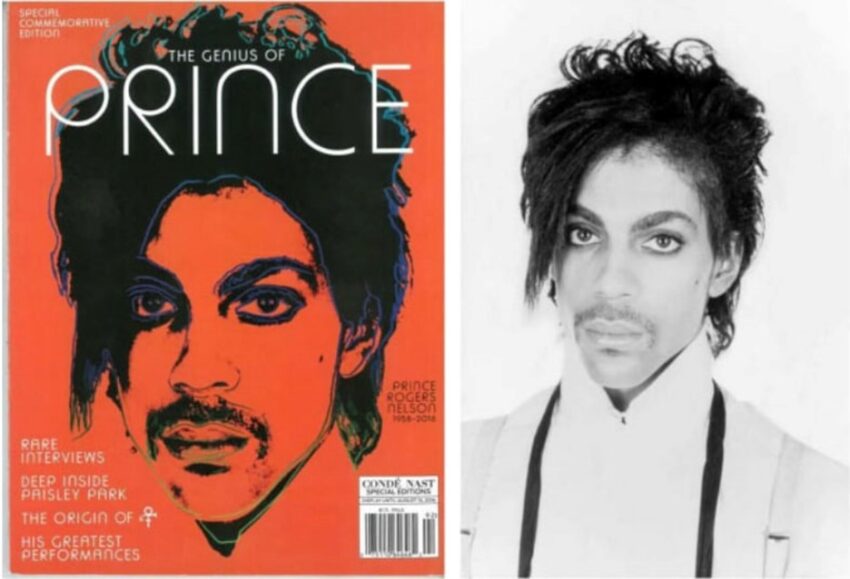

And now, years later, she is the victorious Goldsmith of Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, 143 Supreme Court 1258 (2023)–a decision that attempts to drain that swamp and clear some of the fog of war in the realm of appropriation art. The two images that were at issue in that case are at the top of this post: on the left is the unauthorized “Orange Prince” by Andy Warhol based upon the copyrighted Lynn Goldsmith photograph on the right.

That decision inspired me to write an article for The Common Reader on “fair use” and appropriation art, tracing its origins back not just to the U.S. Constitution but to the Prophet Ecclesiastes. Here is a link. I hope you enjoy it.