This year marks the 50th anniversary of the death of one of the leading literary critics of his time, Edmund Wilson. While many of his readers, especially in academia, admire him as the author of such influential works as To the Finland Station (1940) and Patriotic Gore (1962), for this humble scribe, whose books are found in the Mystery section of your local bookstore or library, the anniversary of his death triggers the memory of two of the nastiest attacks on the mystery genre in American history—attacks that are not merely boorish and condescending but reveal a remarkable level of obliviousness to the fact that some of the great works of Western literature easily fit within the definition of a mystery.

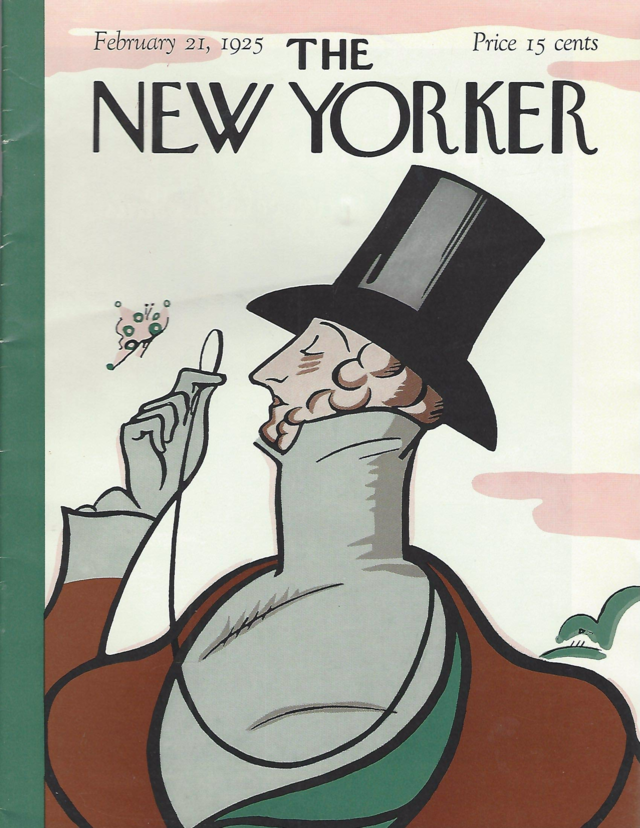

The first of those two essays, published in the October 14, 1944 issue of The New Yorker, is entitled “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?” Wilson explains that he was baffled by all of the enthusiastic fans of mystery novels—a genre he’d abandoned years before. So he decided to give mysteries another try, and he read several of the most popular novels. The result? Well, here’s what he had to say about Agatha Christie’s Death Comes as the End:

“I did not care for Agatha Christie and I hope never to read another of her books. * * * Her writing is of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read.”

Yikes!

Not even Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon escapes his ridicule:

“As a writer, he is surely almost as far below the rank of Rex Stout as Rex Stout is below that of James Cain. The Maltese Falcon today seems not much above I those newspaper picture-strips in which you follow from day to day the ups and downs of a strong-jawed hero and a hardboiled but beautiful adventuress.”

almost as far below the rank of Rex Stout as Rex Stout is below that of James Cain. The Maltese Falcon today seems not much above I those newspaper picture-strips in which you follow from day to day the ups and downs of a strong-jawed hero and a hardboiled but beautiful adventuress.”

As you might imagine—and Wilson acknowledges in his second essay on the topic (published in The New Yorker two months later in January of 1945)—his first article generated dozens of angry letters from readers who claimed to be “deeply offended and shocked,” many of whom told him he would surely change his opinion if he “would only try this or that author recommended by the correspondent.”

And so he did. And? The answer is foreshadowed in the title of that second essay, with its reference to Agatha Christie’s landmark novel. The title? “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?”

And so he did. And? The answer is foreshadowed in the title of that second essay, with its reference to Agatha Christie’s landmark novel. The title? “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?”

As Wilson explains, he read the various mystery novels his angry correspondents had urged him to read. That experience only reaffirmed his belief that reading mysteries is “wasteful of time and degrading to the intellect.” As for those who shared his disdain for the genre, he ends his article with the following exhortation:

“Friends, we represent a minority, but Literature is on our side. With so many fine books to read, so much to be studied and known, there is no need to bore ourselves with this rubbish.”

Wilson was not merely wrong but curiously oblivious to the fact that many of the classic works of literature that had pride of place on his bookshelves were actually classic works of mystery. Here’s why:

A few years ago I wrote an article entitled “Nine Mysteries for Literary Snobs.” In that piece I identified the three requirements for a work of fiction to qualify as mystery:

- An unsolved murder or missing person or thing of value (such as a Maltese Falcon);

- A lone protagonist; and

- A single point of view (either that of our protagonist or a sidekick, such as Dr. Watson).

That 3rd factor is key. In contrast to the thriller genre, where we typically have more than one point of view—including that of the victim, the detective, the serial killer, etc.—in a classic mystery we remain inside the head of our detective from start to finish. Indeed, in many thrillers the reader learns the killer’s identity in the very first chapter. By contrast, the reader of a murder mystery usually discovers the murderer’s identify after the hero does.

Satisfy those three requirements, I explained, and–voila!–you have a mystery. I then set out, in a series of posts, to identify nine “mystery novels” that our literary snobs can locate in the Literature section of their favorite bookstore. Indeed, Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, shelved over in the Mystery section, shares many of the plotline elements of one of those nine classic works of literature, Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness. Conrad’s novella, stripped to its basics, is immediately familiar to fans of The Big Sleep: the search for a powerful missing person, narrated in the first person by a cynical loner who in the end turns out to be a grudging romantic. The missing person in Conrad’s novel is Mr. Kurtz. In Chandler’s novel, it’s Rusty Regan. Even better, both detectives are named Marlowe, albeit Conrad’s drops the final “e.”

Satisfy those three requirements, I explained, and–voila!–you have a mystery. I then set out, in a series of posts, to identify nine “mystery novels” that our literary snobs can locate in the Literature section of their favorite bookstore. Indeed, Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, shelved over in the Mystery section, shares many of the plotline elements of one of those nine classic works of literature, Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness. Conrad’s novella, stripped to its basics, is immediately familiar to fans of The Big Sleep: the search for a powerful missing person, narrated in the first person by a cynical loner who in the end turns out to be a grudging romantic. The missing person in Conrad’s novel is Mr. Kurtz. In Chandler’s novel, it’s Rusty Regan. Even better, both detectives are named Marlowe, albeit Conrad’s drops the final “e.”

Apply my three requirements and you will discover that some of your favorite classic works of literature also qualify as mysteries, going all the way back to the murder mystery at the heart of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. We could remind our snob that William Shakespeare, in his great murder mystery Hamlet, quite literally staged (in Act 2, Scene 3) the archetypal drawing-room denouement by having his indecisive detective hero lure King Claudius into revealing his guilt during the play-within-a-play scene. Hercule Poirot would have been proud.

Apply my three requirements and you will discover that some of your favorite classic works of literature also qualify as mysteries, going all the way back to the murder mystery at the heart of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. We could remind our snob that William Shakespeare, in his great murder mystery Hamlet, quite literally staged (in Act 2, Scene 3) the archetypal drawing-room denouement by having his indecisive detective hero lure King Claudius into revealing his guilt during the play-within-a-play scene. Hercule Poirot would have been proud.

And thus, to rehabilitate Edmund Wilson’s condescending declaration of triumph, “Friends, we represent a minority, but Literature is on our side. With so many fine mysteries to read and be studied and known, there is no need to bore ourselves with these clueless literary snobs!”

Most wonderful article! Thanks for sharing. Also beautifully written.

Such an interesting article. Mike, you always have such amazing insights. Love the ‘turn about is fair play’ ending. Just ordered Bad Trust – love your Rachel Gold!