![O_brother_where_art_thou_ver1[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/O_brother_where_art_thou_ver11-205x300.jpg) Critics have long debated whether the correct number is six or nine or eleven, but they do agree that all literature–no matter the genre–can be reduced to less than 12 basic story lines. Whether you label Homer’s The Odyssey a quest story, a revenge tale, a picaresque adventure, or an astounding melange of all three, its impact on subsequent storytelling has been enormous. In just the past century, Homer’s epic has been the acknowledged inspiration for the Margaret Atwood novella The Penelopiad, the Coen brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou, and the James Joyce novel Ulysses. And certainly the qualities Homer celebrates in Odysseus–wily, courageous, determined, smooth-talking–also describe Philip Marlowe, Spenser, Lew Archer, and many other American detective novel heroes, each of whom sets off on their own odysseys.

Critics have long debated whether the correct number is six or nine or eleven, but they do agree that all literature–no matter the genre–can be reduced to less than 12 basic story lines. Whether you label Homer’s The Odyssey a quest story, a revenge tale, a picaresque adventure, or an astounding melange of all three, its impact on subsequent storytelling has been enormous. In just the past century, Homer’s epic has been the acknowledged inspiration for the Margaret Atwood novella The Penelopiad, the Coen brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou, and the James Joyce novel Ulysses. And certainly the qualities Homer celebrates in Odysseus–wily, courageous, determined, smooth-talking–also describe Philip Marlowe, Spenser, Lew Archer, and many other American detective novel heroes, each of whom sets off on their own odysseys.

But it was only recently that I discovered yet another modern heir of The Odyssey. That epiphany occurred during my drive to the office. I had been listening to the audio version of that epic tale, read brilliantly by Dan Stevens, the actor known better for his role as Mathew Crawley in the PBS series Downtown Abbey.

For those who haven’t read (or have forgotten the details of) The Odyssey, it opens nearly a decade after the Greek-Trojan war. The resourceful Odysseus![ulysses[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ulysses1-192x300.jpg) has been on a difficult quest to return home to Ithaca and to his faithful wife Penelope and only son Telemachus, who was just a toddler when his father left for the war nearly 20 years ago.

has been on a difficult quest to return home to Ithaca and to his faithful wife Penelope and only son Telemachus, who was just a toddler when his father left for the war nearly 20 years ago.

As our hero’s quest takes him on one adventure after another–battling monsters, resisting enchanting witches, visiting shades in the underworld–Homer occasionally cuts back to Ithaca, where Penelope and Telemachus have been forced to share their home with the “Suitors,” a crowd of 108 boisterous, obnoxious young men whose goal is to persuade Penelope to marry one of them, all the while exploiting the hospitality of household and consuming its wine, pigs, and wealth.

Telemachus leaves the island in search of news of his father, who he fears is dead after all these years. Back on Ithaca, Ant![The_Odyssey_by_Homer_53219[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The_Odyssey_by_Homer_532191-205x300.jpg) inous, the leader of the Suitors and a truly creepy, arrogant aristocrat, plots to kill the young man on his return home. But Telemachus evades the ambush and seeks sanctuary in the hut of his father’s loyal swineherd, Eumaeus. And there, to his joy, he is reunited with Odysseus, who has also just returned.

inous, the leader of the Suitors and a truly creepy, arrogant aristocrat, plots to kill the young man on his return home. But Telemachus evades the ambush and seeks sanctuary in the hut of his father’s loyal swineherd, Eumaeus. And there, to his joy, he is reunited with Odysseus, who has also just returned.

That’s the point where the story shifts from epic quest to tale of revenge. And that’s when I had my epiphany. As Telemachus and Odysseus start toward their house and all those rowdy Suitors, I realized that The Odyssey was also the godfather of the American Western movie. Yep. The Odyssey, starring John Wayne or Clint Eastwood.

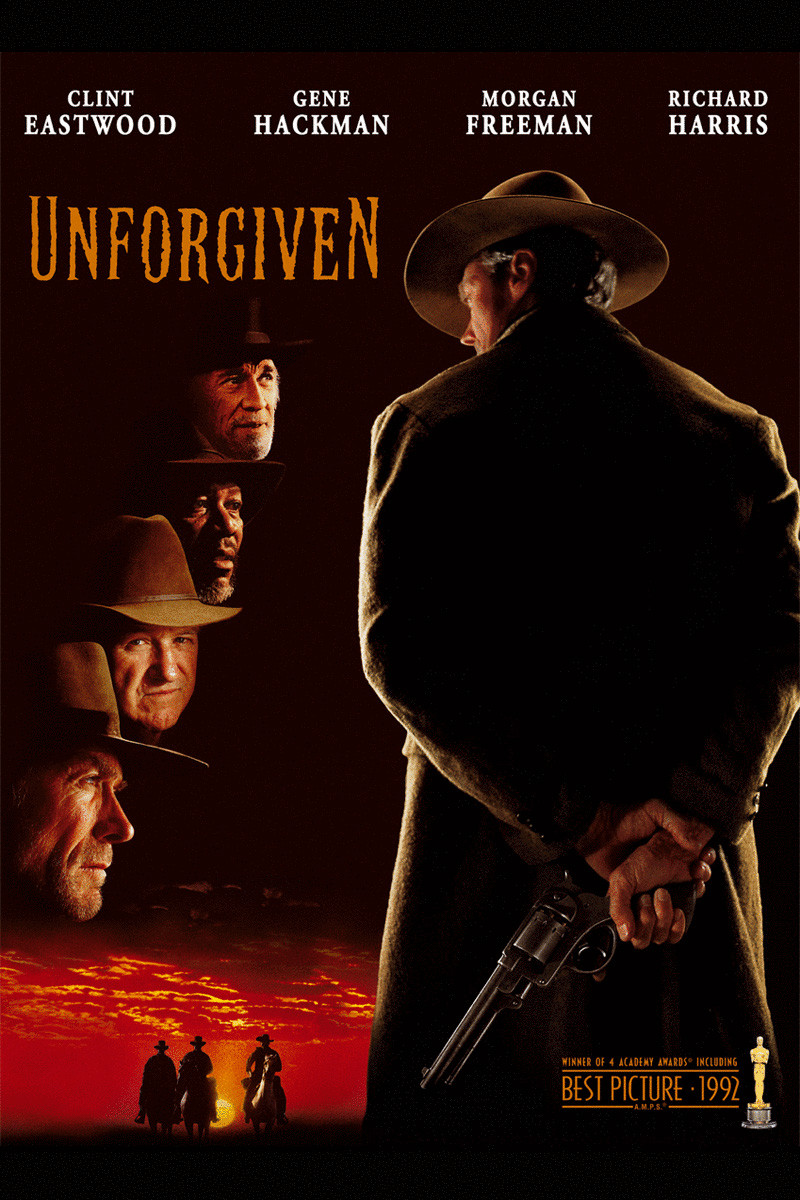

Take, for example, one of my favorite movies, The Unforgiven. That final battle scene in the saloon between the gunslinger William Munny (Clint Eastwood) and the followers of Little Bill Dagget (Gene Hackman) echos the final battle scene in the Great Hall between Odysseus and followers of Antinous.

Odysseus enters the Great Hall disguised as an old man, and is immediately mocked by Antinous and the other Suitors. But after surprising them by winning a contest of strength, he throws off his disguise, grabs his bow and arrows, and cries, “But another target’s left that no one has hit before. We’ll see if I can hit it–Apollo give me glory!”

And then, in a battle scene that echoes the final gun battle in The Unforgiven, Odysseus take his bloody revenge. Here’s how it begins (in the Robert Fagles translation):

With that he trained a stabbing arrow on Antinous . . . just lifting a gorgeous golden loving-cup in his hands, just tilting the two handled goblet to his lips, about to drain the wine–and slaughter the last thing on that suitor’s mind. Who could dream that one foe in that crown of feasters, however great his power, would bring death down on himself, and black doom?

But Odysseus aimed and shot Antinous square in the throat, and the point went stabbing clean through the soft neck and out

–and off to the side he pitched, the cup dropped from his grasp as the shaft sank home, and the man’s life blood came spurting from his nostrils–

thick red jets–

a sudden thrust of his foot–

he kicked away the table–food showered across the floor, the bread and meats soaked in a swirl of bloody filth.

The suitors burst into an uproar all throughout the house when they saw their leader down.

And, as with Little Bill and his doomed posse in The Unforgiven three millennia later, the slaughter has only begun. The message is the same in both: don’t mess with Odysseus, and don’t mess with Clint Eastwood.