While out in Phoenix last week I had the pleasure of spending a delightful afternoon with two of my book publishing heroes: Barbara Peters and Rob Rosenwald, the founders of Poison Pen Press. While sipping Rob’s amazing limoncello, which he creates with fruit from the lemon tree in their backyard, our conversation drifted, as you might expect, toward books. And in particular, the import role played by the opening paragraph–a topic I had discussed here a few years ago in the context of short stories. For a novel, that opening paragraph is the literary version of foreplay in which the author–and the publisher–hope to get their potential reader in the mood.

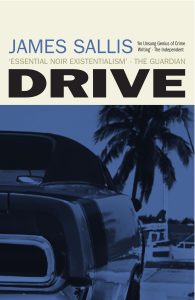

Rob read to me his favorite opening paragraph of all time, which he first saw in the manuscript for a thriller. He was so blown away by that paragraph that he was able to convince the author James Sallis to allow Poison Pen Press to publish that novel, Drive. That opening paragraph reads as follows:

Much later, as he sat with his back against an inside wall of a Motel 6 just north of Phoenix, watching the pool of blood lap toward him, Driver would wonder whether he had made a terrible mistake. Later still, of course, there’d be no doubt. But for now Driver is, as they say, in the moment. And the moment includes this blood lapping toward him, the pressure of dawn’s late light at windows and door, traffic sounds from the interstate nearby, the sound of someone weeping in the next room.

I was hooked! I read the novel as soon as I got back home–and it was terrific.

But it got me thinking about some other favorite opening paragraphs from novels I love. In each case, the opening sentence–like a great opening line in a singles bar–catches your attention. But what follows in the rest of that first paragraph is just as important if you, as the author, hope your reader wants to take you home. Here are just a few:

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain: You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. That is nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another, without it was Aunt Polly, or the widow, or maybe Mary. Aunt Polly – Tom’s Aunt Polly, she is – and Mary, and the Widow Douglas is all told about in that book, which is mostly a true book, with some stretchers, as I said before.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson: We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive….” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming: “Holy Jesus! What are these goddamn animals?”

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson: We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive….” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming: “Holy Jesus! What are these goddamn animals?”- Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler: It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler: It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

My list goes on. But I wanted to end this with two truly unique opening paragraphs–one that tends to get lost in the shuffle because of the fame of its opening line and the other that has spawned an entire cottage industry of celebrators and dissectors.

The first is Moby Dick, which probably has the most famous opening line of all American literature. But that opening line only gets you to the second sentence–and as the Mark Twain example above demonstrates, that second sentence better not drop the proverbial ball. What’s remarkable about the lines that follow “Call me Ishmael” is how they lure you into the story:

The first is Moby Dick, which probably has the most famous opening line of all American literature. But that opening line only gets you to the second sentence–and as the Mark Twain example above demonstrates, that second sentence better not drop the proverbial ball. What’s remarkable about the lines that follow “Call me Ishmael” is how they lure you into the story:

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago — never mind how long precisely — having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off — then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.

And the second is the opening paragraph of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, which has, as noted above, generated a cottage industry of analyzers and celebrators. Here is a link to just one of them. Do a Google search for “a farewell to  arms opening paragraph” and prepare to descend into a rabbit hole of commentary. But first, here is that opener:

arms opening paragraph” and prepare to descend into a rabbit hole of commentary. But first, here is that opener:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

Okay, readers. Any other openers you’d like to share?

Love it. And I do agree the Chandler is near the top of the list, but I still think that Drive’s opening paragraph sets a scene that one must investigate further

Agreed, Rob. Sallis does an outstanding job on every level. His final chapter and final couple paragraphs are so powerful in their own unique way.