I have written here and elsewhere of the power of a great opening line. If you can imagine a bookstore as a crowded singles bar with each book hoping to get lucky, that first sentence essentially functions as the author’s pick-up line. Sure, a sexy book jacket helps, since it will increase your chances of getting pulled off the shelf. But as the old saying goes, you can’t judge a book by its cover. And thus when that curious reader opens to page 1, your odds greatly improve if you can start with something original and enticing.

Leo Tolstoy did it with Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” And Jane Austen most certainly did it with Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” They are hardly alone . The Internet is filled with lists of great opening lines, such as this Top 100 from the American Book Review and this Top 30 from The Telegraph.

. The Internet is filled with lists of great opening lines, such as this Top 100 from the American Book Review and this Top 30 from The Telegraph.

Lately, though, I’ve been thinking about an even more powerful seduction tool: the opening paragraph. Many of the great opening lines, including the two quoted above and, of course, “Call me Ishmael,” stand alone. Literally. They are one-sentence paragraphs. Yes, they catch your attention–much like that snappy pick-up line in the singles bar. But then, well, you need to start all over again.

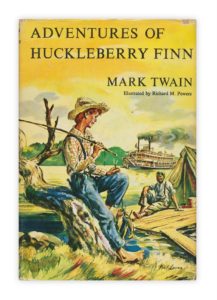

The real magic takes place in a great opening paragraph. A real paragraph. Not just a one-liner. And what makes an opening paragraph great? The magical lure of the narrator’s voice. Take, for example, the greatest opening paragraph in American literature:

You don’t know about me, without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. That is nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another, without it was Aunt Polly, or the widow, or maybe Mary. Aunt Polly—Tom’s Aunt Polly, she is—and Mary, and the Widow Douglas is all told about in that book, which is mostly a true book, with some stretchers, as I said before.

Or this droll opening paragraph of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep:

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved, and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

Two very different opening paragraphs, two very different novels, but both sharing something vital: a distinct and intriguing narrator voice. And while Huck Finn and Philip Marlowe share little else in common, those two opening paragraphs have drawn millions of readers into their stories.

In mulling over great opening paragraphs, I came to another realization: almost all are written in the first person. That’s Huck’s voice we hear. And Philip Marlowe’s voice. Those opening paragraphs achieve a special intimacy between the reader and the narrator. The same is true for so many other great opening paragraphs–from Pip (in Great Expectations ) and David Copperfield to Holden Caulfield and Augie March and so on and so on. Pick your favorite opening paragraph and odds are its narrated in the first person, and often by the protagonist. (We can let the critics debate whether Nick Carraway is the real protagonist in The Great Gatsby.)

I confess that I, too, have succumbed to the lure of the opening paragraph. One example comes from my novel Firm Ambitions:

I confess that I, too, have succumbed to the lure of the opening paragraph. One example comes from my novel Firm Ambitions:

Despite the allegations in the petition, fellatio is no longer included in Missouri’s list of infamous crimes against nature. It remains, however, “deviate sexual intercourse,” which the criminal code defines as “any sexual act involving the genitals of one person and the mouth or tongue of another.” The code calls it a class A misdemeanor. Vicki McDonald calls it a Big Mac with Special Sauce.

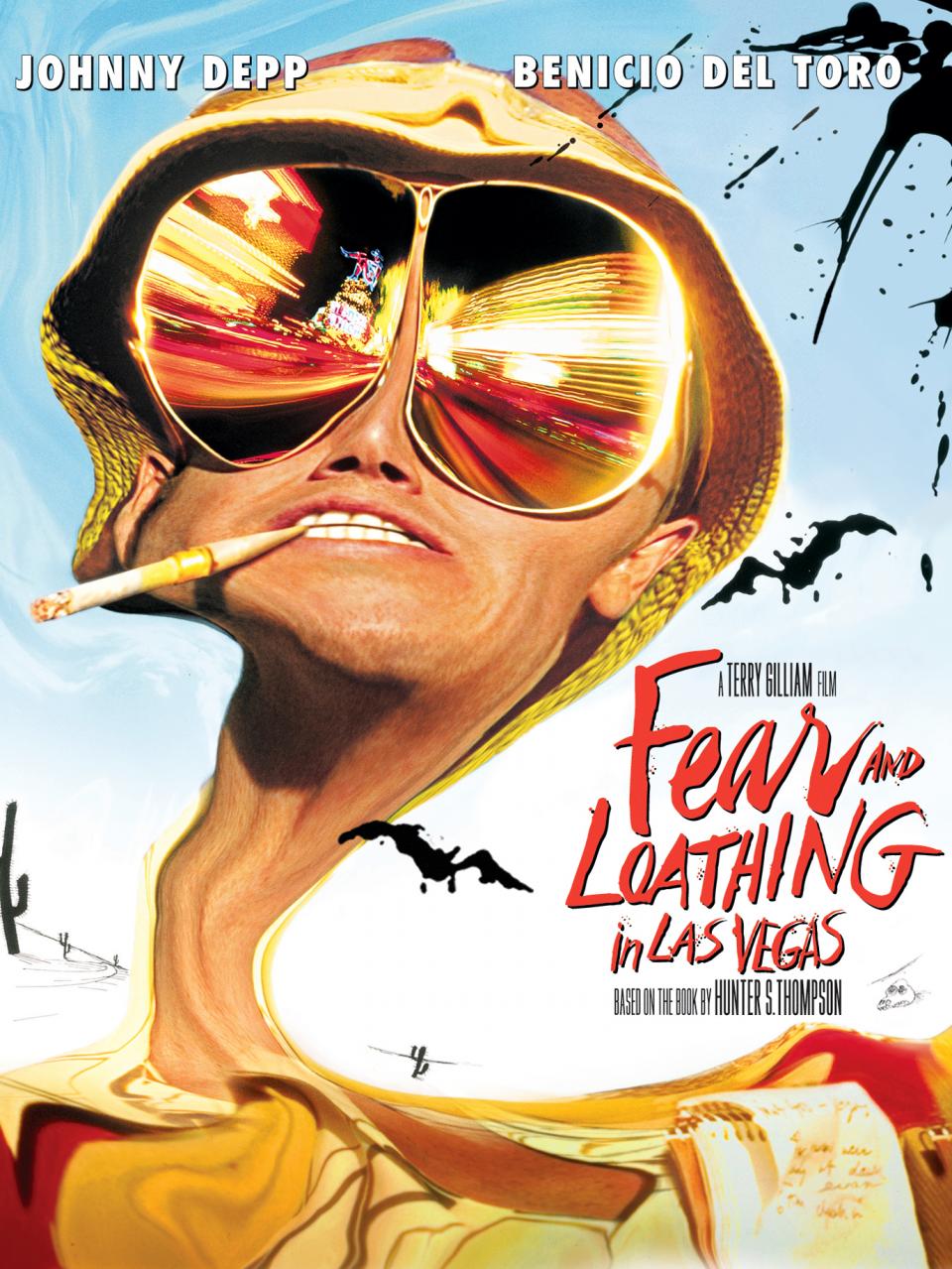

And finally, no serious discussion of great opening paragraphs can ignore the Grandmaster of Gonzo Journalism, Hunter Thompson, who opened Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas with the greatest first paragraph since Huckleberry Finn and thus provides us with a perfect closing paragraph here. As with Mark Twain’s opener, it’s hard to imagine any reader coming to the end of Thompson’s first paragraph and not continuing on to the second. Enjoy!

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive. . . .” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming: “Holy Jesus, what are these goddam animals?”